Acer Aspire & the UEFI Blues

Published on 2017-10-10 by Tristan Sweeney

Prologue

A year and a half ago, I bought an Acer Aspire laptop (model number E5-573G-79HX), which recently experienced a hard shutdown and consequently experienced a hard disk failure, after which I replaced the HDD and installed ArchLinux. Following the manual instructions from ARCH WIKI, I was able to partition and format disks, setup my fstab file, configure the wireless interface, add users, and bring up a desktop environment from scratch.

I discovered on reboot that my laptop didn’t ‘see’ the Arch installation. I found a solution that required using the UEFI shell to write a boot entry to the laptop’s NVRAM, because the motherboard’s BIOS will properly load all EFI partitions but won’t discover the grubx64.efi which kicks off loading the GRUB bootloader. I suspect the BIOS won’t search for any .efi files outside those it expects from Windows, but can’t prove that.

Backstory

Act 1: Twin Sunrise

I discovered several months ago that my Laptop, an Acer Aspire that I bought sometime last May, had a battery-life problem. Any time that I unplugged the laptop it immediately lost power and did a hard shutdown, which is not the behavior that you want in a mobile device at all. Luckily, this fault happened sometime before or during my co-op at Amazon Robotics, and I had a work laptop provided to me which filled the niche of wanting to work while not tethered to a wall outlet. I cherished that laptop, which was some HP Z-Book, but alas a month ago my time at Amazon ended and I headed back into classwork, and back into the arms of my scorned ex-laptop.

To the Acer’s credit it didn’t fall apart from the occasional accidental hard reset from a jostled power cable for a whole month.

Act 2: That’s no Moon

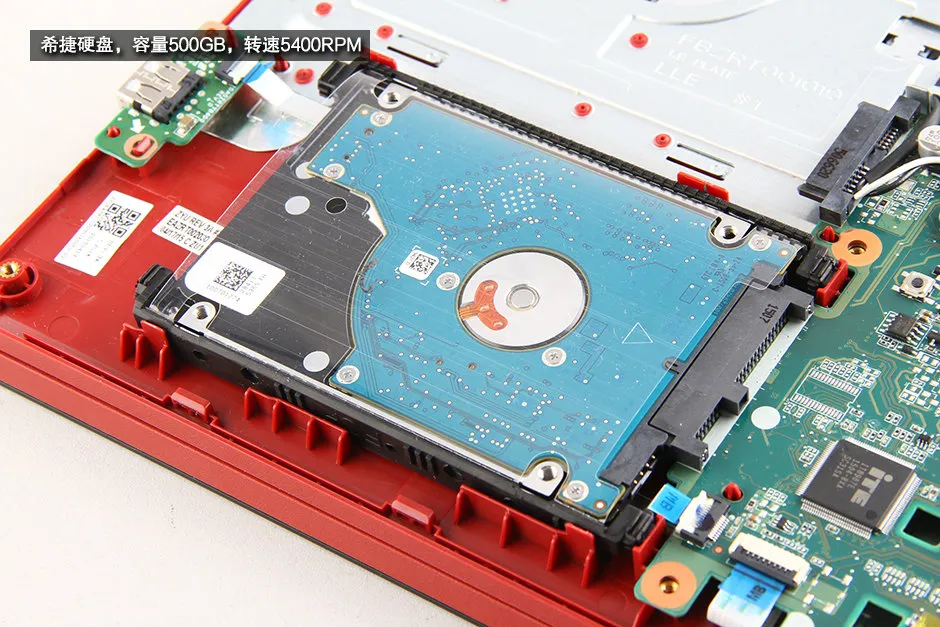

To pose a riddle, what spins at 5400 rpm and absolutely wrecked my plans two weekends ago? The answer, which will surprise nobody, is my laptop’s hard disk. My accidental study into the Mean-Time-To-Failure of a hard disk under extreme misuse found that it only takes a month for a hard disk to fail. A quick test running badblocks from an Arch live USB confirmed I was now the owner of one very expensive paperweight.

Luckily (unluckily?) I have broken laptops in the past, and had a 1 TB hard disk from a Sony Vaio on hand. It looked like it had a proprietary connector, but that was just a SATA adaptor that was held onto the drive with an adhesive metal tape. Peeling that tape off and removing the adaptor left a perfect replacement drive, which I was able to quickly swap out thanks to Acer’s pretty simple HDD caddy. It’s just flexible rubber caddy that fits a 2.5” HDD like a glove, making replacing the HDD take less than ten seconds once the laptop’s case is opened up (which takes about 5 minutes if you’re taking your time to avoid having a screw fly off into oblivion).

The adaptor I pulled off of my old laptop’s HDD.

The HDD assembly in my Acer, more elegant than what I was expecting! (must be from a more civilized age)

Once I had the HDD replaced I went through the Arch installation process detailed at ARCH WIKI. It was great, after all the time I’ve spent working with Linux systems it was fulfilling doing something that has always been chalked up to be hardcore and think it was fun rather than impossible. Once I had an XServer set up and XFCE (a lightweight desktop environment) set up on top of it, I decided that was enough tampering and was happy.

I rebooted my laptop and removed the live USB. That’s when I discovered things hadn’t gone as planned.

Act 3: Red Five Standing By

A quick layman’s history on HDDs and the boot sequence. There are two partitioning schemes, Master Boot Record (MBR) and Globally Unique Identifier (GUID) Partition Table (GPT). GPT is now the standard partitioning scheme, because it’s much more flexible.

When the motherboard’s BIOS is in Legacy mode it operates with MBR, and looks for a boot record in the first 512 bytes of the disk to execute. This is a rather simple scheme to adhere to, and a stub of code would be written to that boot-record space to jump to an OS bootloader somewhere else on the disk (or you’d install your own bootloader such as GRUB if you were feeling fancy). However, the MBR scheme is actually pretty restricted, both by boot-record size and the fact it only supports 4 partitions. Also, in a dual-boot system you could have one OS continually override the bootloader’s MBR entry (looking at you here Windows).

When the motherboard’s BIOS is in UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) mode, it ideally looks through all the partitions on each HDD and identifies the partitions which are typed as ‘EFI Bootable’, and presents each of those partitions as a bootable device. Your BIOS boot order would dictate which you booted into by default, and in the case of most linux installs that would boot into a GRUB installation which broke out boot options for you. This scheme is pretty elegant.

Laptop manufacturers sometime don’t make it work though.

Finale: Trench Run

A vast majority of laptops run Windows. Mine did, and does again (If I leave linux installed I tinker too much with it). That’s fine, grumbling about Windows aside, but the problem is it lets laptop manufacturers be lazy and not properly implement the part of the UEFI interface where it scans for EFI partitions, and then scans those partitions for .efi files to boot. Luckily, there’s an easy fix here (easy? I wrote this much background! It’s a bit I need to demonstrate that I’m technically competent for employment in the future and a lot me procrastinating), and that fix is to boot into a UEFI shell and manually identify where in NVRAM the .efi file lives.

bcfg boot dump -vbcfg boot add 1 fs0:\EFI\arch\grubx64.efi "Arch Linux (grub manually added)"exitIt’s a pretty simple fix, and it’s documented on the Arch Wiki, but it wasn’t ever called out as a fix to a magic “Your device doesn’t boot even though you followed the installation procedure” problem. Hopefully this post finds some Acer Aspire owner out there pulling his hair out over no-boot-device found messages after taking the time to set up an Arch system!

Written by Tristan Sweeney

← Back to blog